March 2018

A research project simulating the evolution of virtual corals. Corals are grown in underwater environments containing light and current flow and are evolved with a genetic-algorithm. Morphogens, signaling, memory and other biologically motivated capacities enable a multipurpose biomimetic form optimization engine. This work is part of a series of projects exploring emergent and generative forms.

Corals are not plants but rather colonies of genetically identical organisms called polyps, which are attached to one another and act as a single entity. Polyps are genetically very similar to jellyfish. Like jellyfish they collect nutrients from a symbiotic relationship with photosynthetic bacteria called Zooxanthellae living inside them. The polyps also catch small plankton floating by. Polyps from stony-corals deposit calcium beneath themselves, and this produces their structures. There are many different types of corals with varying forms and home environments. Some do not consume Zooxanthellae and others do so entirely.

The intent of this work was to use the underwater environments and coral biology as guidelines for testing a method for optimization of form. The creation of and control over optimized and emergent forms, not limited by training data, interests me for its many potential applications in art, design and engineering and even potentially studying evolution. This work is not intended as a precise mimic of coral biology.

Drag to rotate, right click and drag to pan.

Click on a coral to watch it grow.

Add Coral

Colors represent the multiple evolved morphogens (more on that later).

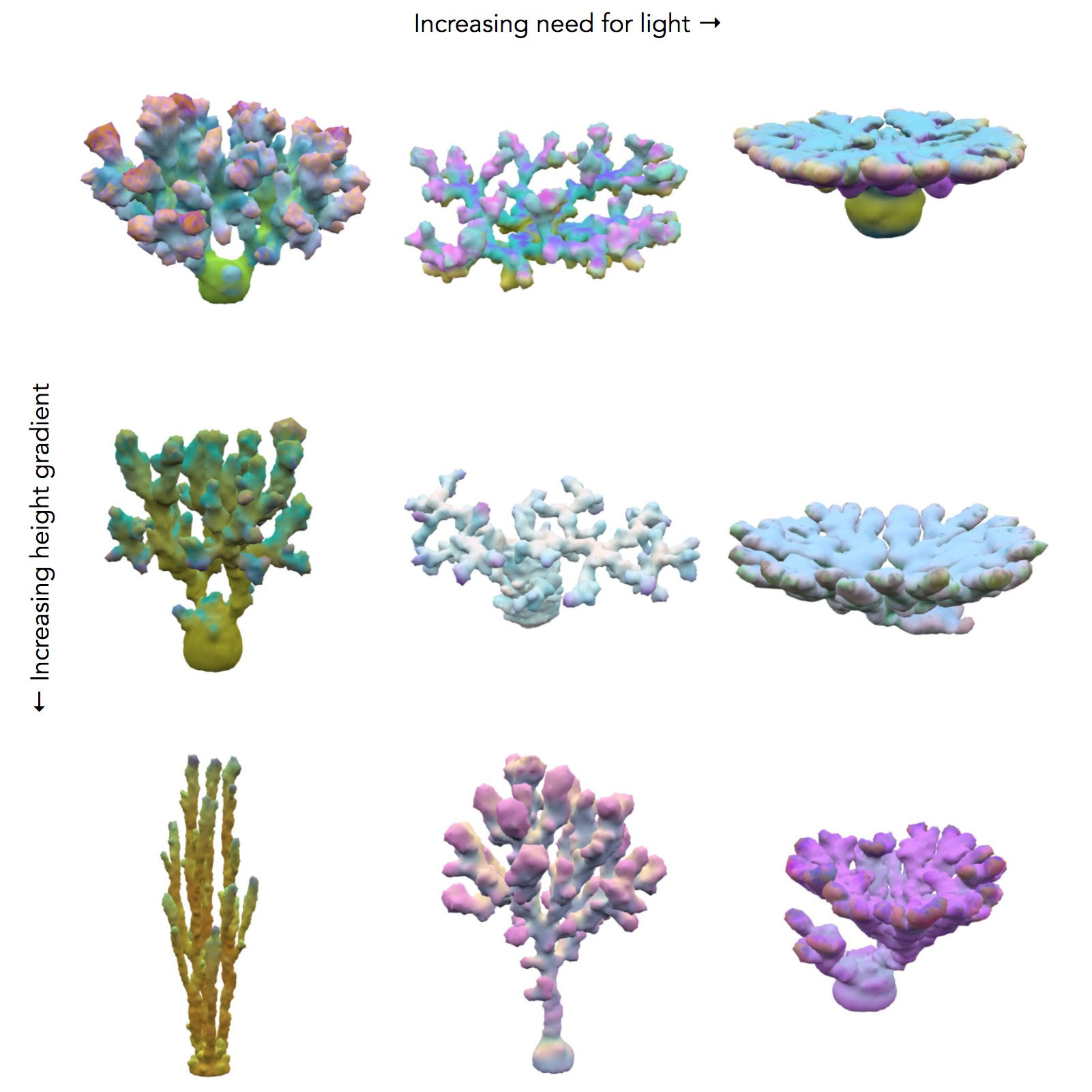

Each coral consumes ~10MB of data.

The evolution of corals were run in varying environments. In the results below, the environments are identical except for the depth below the surface and the relative need for light versus plankton. In shallow coral environments both plankton and light decrease with depth. The height of this gradient is varied along with the need for light versus plankton. For most environments there was a large amount of diversity of the forms, except for those which needed a lot of light which tended to converge on flat shapes. The colors represent the levels and distributions of different signal morphogens and reaction-diffusion interactions, details below.

Genetic algorithms mimic evolution by starting with random solutions to a problem and then applying random mutation with selection, which is repeated for many generations. The less optimized corals from earlier generations are are often much wilder and weirder. Each of the dozens of runs produced an interesting evolutionary progression, so I have picked some randomly to showcase.

Drag the slider to see the change over evolution. The initial corals are the best of the first generation and, when dragged to the end, are the best of the last generation.

This is not exhaustive and focuses on works that were inspirational.

My research interest is how growth enables complexity by expanding - or decoding - the genotype into the phenotype. Within computer science this emergent mapping is often studied in the context of the complexity of the networks themselves. For example, HyperNEAT[1] is a neuroevolution method that uses a compositional pattern-producing network (CPPN) to map a smaller network to a larger one. CPPN's are a state of the art method for generating images[2], forms[3] and soft robots[4]. This mapping has also previously been studied under the name embryogenesis [5, 6]. Bentley [5] defines three main types of embryogenies: external, explicit and implicit. External are user defined direct mappings with no growth, explicit are directly defined growth steps such as Lindenmayer and generative growth grammars, and implicit do not explicitly define growth rules and emerge from multiple interacting and indirect rules.

Karl Sims iconic virtual creatures[7] from 1994 was an inspiration for many people in the field. He was the first to popularize genetic algorithms for creative applications and utilized a novel genome growth process. Twenty-four years later, the fact that it is still among the most iconic works in this field is indicative of how ahead of its time it was (and perhaps how little progress there has been since.)

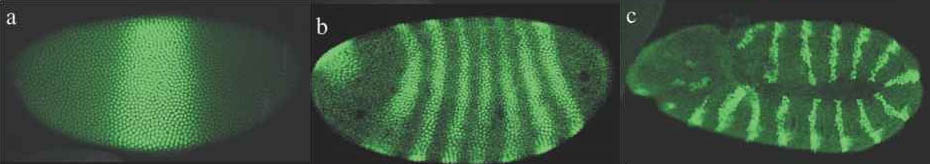

Growth and development are, unsurprisingly, mostly studied by biologists who employ modeling systems to help understand the emergence of biological complexity and life within the subfield of developmental biology. Mathematician Alan Turing first formulated how interacting molecules, called morphogens, could establish chemical gradients through a process called reaction-diffusion that would allow patterns to arise in otherwise homogeneous cells. While exact biological relevance of reaction-diffusion is debated, the use of long range patterns and gradient are necessary for all biological development [8, 9, 10]. There have been many cell growth models developed using various cell representations and cell ability such as signal transduction, memory and morphogens [11, 12, 13, 14]. The French Flag Model is a framework for visualizing and investigating mechanisms of pattern formation during development. A good, if somewhat outdated summary of the research for a computer science audience is [15].

Above, morphogen patterns in drosophila wing development.

Ultimately, there is much less utility in studying a biological system that has not been optimized, much like an alien studying a computer that has no software or firmware on it. Scientists may find value in incorporating gradient-free optimizations such as genetic algorithms in their biological models.

Historically, artistic generative plant modeling has primarily used L-systems and other formal grammars (explicit embryogenies) to create fractal-like patterns[16]. These approaches produce wonderful patterns but are limited within a narrow range of shapes. Additionally, they attempt to mimic the forms and not the processes that give rise to them. Recently, there has been an incredible increase in the complexity and beauty of artistic emergent forms that are biologically inspired. This has been helped by the increased accessibility of both 3D printing and parallel/GPU computing resources available to artists. Andy Lomas uses GPU spring systems to grow massive sculptural cellular forms [17]. He recently gave a great TED talk on his work. The company Nervous System creates generative design systems inspired by plant venation and growth models. These systems produce beautiful 3D-printed jewelry, lamps, clothing and other items. They have been leaders in both applying generative models to functional items and using these generative systems to make the design process interactive (https://n-e-r-v-o-u-s.com/labs/). Finally, Christoph Bader and Dominik Kolb, of both Mediated Matter and deskriptiv, have produced multiple mind-boggling methods for generating immensely complex 3D printed designs [18].

The generative method used here was inspired by experiments I did applying iteration to image producing CPPNs. The CPPN would use the last pixel and past neighbor states for input - essentially a game of life with evolved rules. The dynamic range of patterns with iterative CPPNs was much greater than for regular CPPNs with the same network size, and they performed better too. These experiments reinforced the necessity of iteration and/or permutation for any embryogenesis. This generative mesh method is essentially an iterative CPPN on a mesh.

Each genome consists of a neural network and vector of attributes. The forms are grown by starting with a seed mesh and using the network to control the growth of every vertex (here representing a polyp) at every growth step. The network also controls the output of reaction-diffusion morphogens and vertex-vertex signaling that allows emergent patterns to direct growth. The attributes control global properties, such as decay rates for morphogens, signals and nutrients.

Above is an example random network for a genome with two reaction diffusion morphogens and three signal morphogens. There are corresponding inputs and outputs for each of the morphogens and inputs for the attributes. The network does not begin with any hidden nodes but, using NEAT, may evolve them.

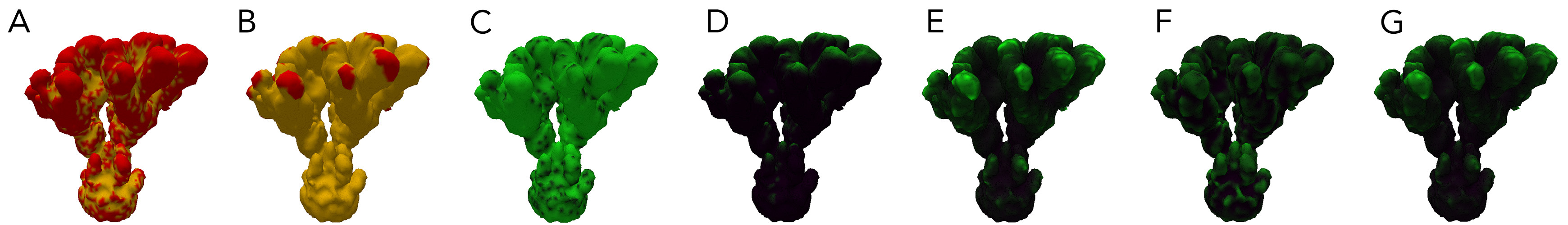

The attributes of each vertex of the mesh. A: Signal0. B: Signal1. C: RD1. D: Light. E: Nutrient Collection. F Curvature: G: Energy.

A genome also has several attributes. Each morphogen system has multiple corresponding attributes for diffusion and decay. The reaction-diffusion morphogens (more below) have attributes for all of their properties. Additionally, each coral has a nutrient diffusion rate that controls how much nutrients polyps share with their neighbors.

The networks are evolved using a genetic algorithm for neural networks (neural-evolution) called NEAT[19]. The version used also allows arbitrary attributes to be evolved independent of the network.

Additionally, a related method called Novelty Search[20] is used with NEAT. Novelty search is a fascinating optimization method that operates under the belief that search spaces are deceptive and abandoning objectives and pursuing the most novel things will paradoxically also produce the best ones. This is a belief that has far-reaching applications to all things involving goals. Novelty changes the fitness function of the optimization to reward novelty. Practically speaking, however, this fails on very sparse search spaces. Thus, a hybrid method was taken based on [21] where fitness and novelty are both used. However, the geometric mean of fitness and novelty was taken over the arithmetic mean used in the paper since the fitness was not normalized or in the same range.

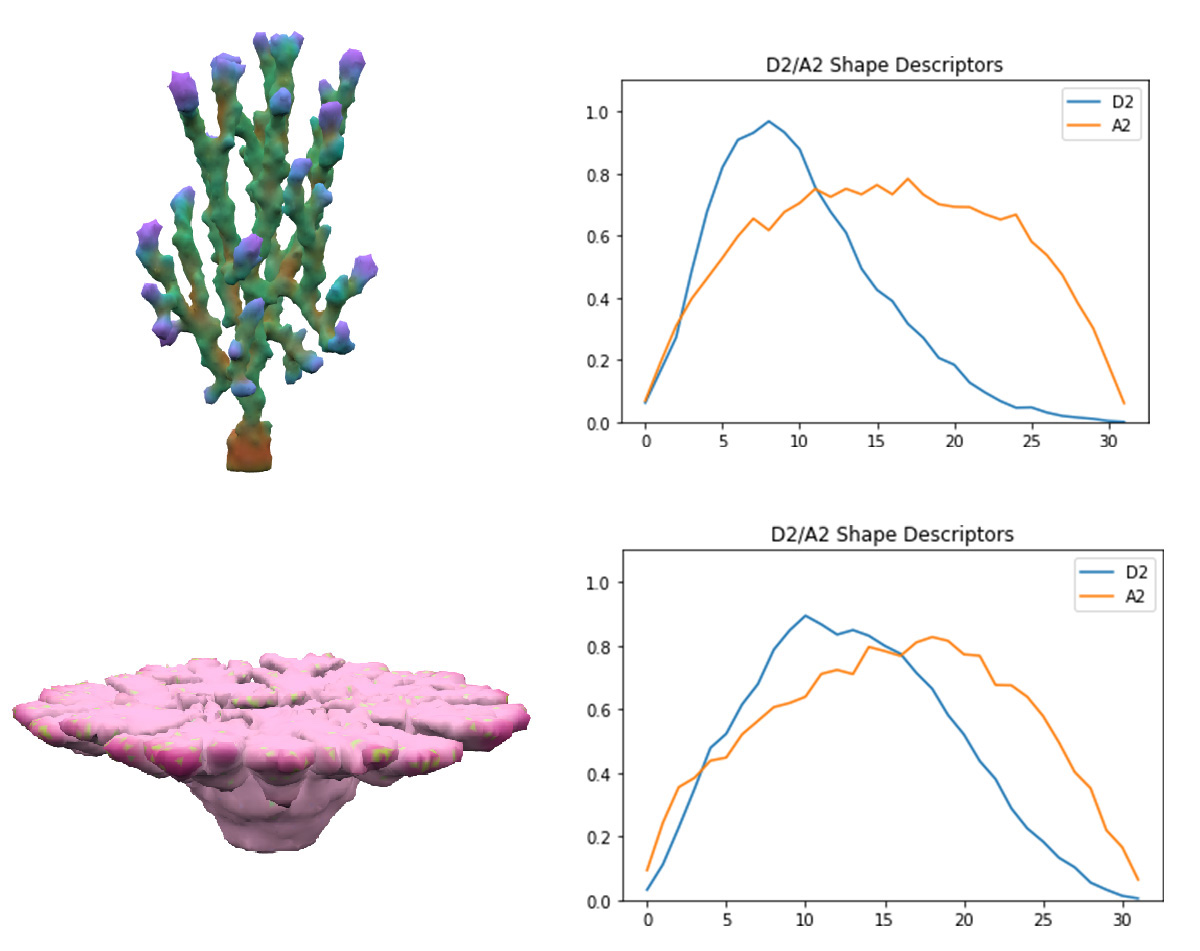

The challenge of employing novelty search was creating a good metric of how different two corals are. This required creating a vector of features for each coral that could be used in nearest-neighbor search. Describing a 3D coral in away that was rotation and position invariant was challenging and I fortunately stumbled into the world of 3D shape descriptors which try to describe a mesh. Their research is primarily motivated by allowing queries of 3D model databases. I used the D2 shape descriptor described here[22], which is the histogram of normalized distances between random pairs of points on the mesh surface. This wonderfully elegant method captures many properties of the shape and is rotation and translation invariant. Additionally, an A2 shape descriptor is used as well which is a similar histogram of the angles between the normal vectors of random pairs. The total feature vector is a thirty-two dimensional descriptor appended to a thirty-two dimensional A2. I have not found another use of shape descriptors for novelty search, but it's a obvious pairing. The comparison of NEAT with and without Novelty Search is discussed below.

Corals on the left with their corresponding shape descriptors on the right. All shape descriptors used 32 dimensions with 214 points sampled for both A2 and D2.

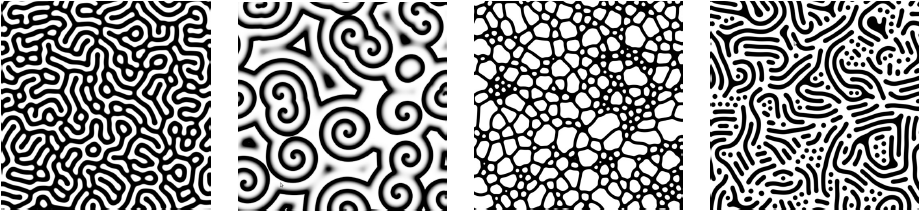

Morphogens are chemicals that give rise to pattern formation during development. Reaction-diffusion is one set of equations that describe the interaction of multiple chemicals that may be used as morphogens. Varying the properties of two (U & V) chemicals can give rise to the patterns seen below and are used commonly for artistic purposes. I used Gray-Scott over others (such as Gierer–Meinhardt) because I found it to be more stable and its parameter space was also well documented. Given more time, I would love to explore the relative efficacy of each model.

From karlsims.com

Each polyp has one input for the chemical U and one output for the chemical V. If the U chemical at the polyp is greater than 0.5, the input is set to 1; otherwise, it is set to -1. Likewise, if a morphogen output is greater than 0.5, the corresponding V is set to 1. Gray-Scott has four parameters which are evolved: the feed rate of chemical U, the kill rate of chemical V, and the decay rates of both.

In addition to reaction diffusion, there is another type of morphogens called signals which simply diffuse. These have evolved decay and diffusion rates allowing them to act as short range communication. Differentiation is an important part in growth and differentiation is a type of memory. Signaling is generalized to include memory because signals may evolve a range of zero.

Light is a simple vertical directional light. I use a spatial hash in the XZ plane to check for every vertex to see if there is another face above it. If not, the light is the angle incident to vertical. For angled lights, I rotate all points around the X or Z axis. Light and shadows are givens in most graphics libraries; however, I could not find a good CPU algorithm reference. Ideally, this would include ambient and diffuse light.

A fast and simple estimate was used for nutrient collection that did not require running a full fluid simulation, although a fast fluid simulation estimate was developed too. The grid is voxelized, and nutrient collection rates are calculated for the grid. The nutrient value for a voxel is inverse to the number of vertices that are within distance radius of that voxel.

Ni is the nutrients at voxel i, dij is the distance between voxels i and j, Oi indicates if voxel i is occupied, and vn is the number of vertices within radius of voxel i. Then, the collection value for all polyps in a given voxel Ci is the average of the nutrient values within that same competitive radius.

Ci is the collection of voxel I and n is the number of voxels within the radius.

Although making d a binary produced similar results with a smaller radius.

The other method tested involved a modified and iterative Dijkstra's algorithm which allowed for directed current flows. Not even a poor man's fluid simulation, this is broke man's simulation. Paths are calculated from every voxel on one side of the grid to any point on the other. The travel costs of every position are then increased proportional the average amount of flow. The results of this method are not shown in this post. It produced a lower diversity of corals, most of which were fan shapes. I am currently working on hybrid methods that have local competition and directed flow.

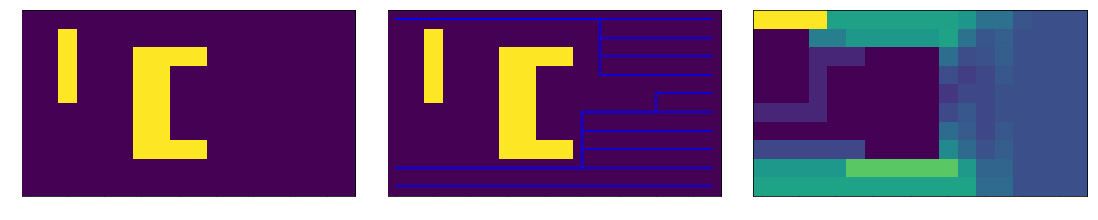

Left: Example obstacles in grid. Middle: Dijkstra's pathing after first iteration where costs are uniform. Right: average current flow after 5 iterations.

The few academic papers on coral modeling use some type of lattice-Boltzmann algorithm[23, 24]; however, it would be prohibitively slow to simulate a large grid for each growth step of each coral in the population for each generation even with a GPU implementation. I also attempted fast fluid simulations for games, which was also too slow.

The academic papers on coral modeling only simulate a single coral at once, and spend several hours doing so. Here, to test the effects of evolution, about ten thousand corals must be simulated per optimization. Although, [23] multiplies vertex collection rates by its surface curvature in order to get a realistic effect indicating the fluid simulations are not ideal.

For corals with greater than three morphogens, the first three principal components were taken, scaled to [0,1] and assigned to blue, red and green respectively. For reaction diffusion morphogens, the U component was used as the value. In this work, there were five total morphogens, and the total variance of first three components ranged between 90% and 99%.

The fitness of a coral is the total amount of energy produced at the end of growth. Limiting the volume and scaling growth by energy prevents uncontrolled growth. For novelty search, the fitness is the square root of the regular fitness times novelty where novelty is the Euclidean distance of the shape descriptor from its ten nearest neighbors.

Corals were run with NEAT for 100 generations with a population size of 80. For Novelty Search, a population size of 20 was run for 400 generations. Corals were allowed up to 15,000 vertices in addition to a max volume and 150 max growth steps. Two main simulation parameters were varied across experiments: light_amount and gradient_height. Twelve pairs of corresponding NEAT and Novelty runs were done with variations of those two parameters such that each run within a pair had exactly the same simulation and evolution parameters. A dynamic novelty threshold was used for adding corals the archive, and no maximum archive size was used. K was 10 for nearest neighbors.

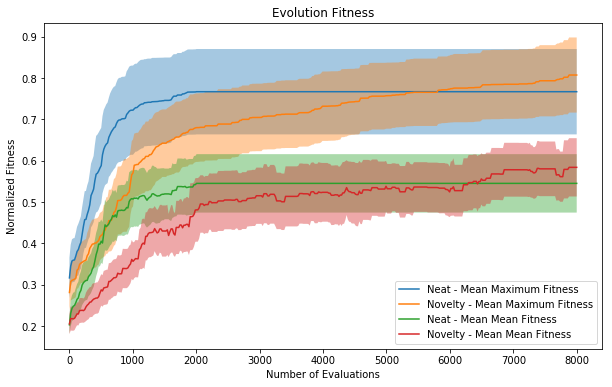

Plots of the fitness of the average and best member of a population averaged across all runs. Each fitness is normalized by the maximum fitness found within a run with the same parameters. This normalization controls for some environments being more challenging than others. Because novelty search had a smaller population size for more generations, the x axis is normalized for total number of corals evaluated. Error bars are 0.5 sigma.

The normal NEAT runs optimize more quickly than with Novelty Search; however, they quickly stagnate and fail to keep evolving after a short period (roughly evaluation 2000, generation 25). The Novelty Search runs slow down slightly relative to the NEAT ones and continue to increase without plateauing. By evaluation 8000, the Novelty Search is roughly 5% better than without. However, this would be improved by more generation and how long they continue to improve will be checked in further work, but this indicates the corals shown are potentially far from fully optimized.

Given the limited abilities of each polyp and simplicity of the networks, I was pleasantly surprised with the results - both the ability of the forms to evolve and the diversity of corals produced. For genomes with less than 100 dimensions, complex forms with ~15,000 vertices are generated, and easily many more if allowed to run longer. Additionally, the results validated the benefits of Novelty Search and the efficacy of the shape descriptors as feature vectors. It makes sense that Novelty Search will optimize more slowly at first due to exploring a larger feature space which is then rewarded by increased robustness to local optimum.

Form, growth, evolution and environment are all linked, making it hard to understand one removed from the others. L-systems and elegant mathematical formulations may help to describe the patterns present in biology; however, plants and growth are not mathematical equations. They are a thoroughly optimized genome emergent in billions of coordinating cells adapting to their environments. Mimicking the methods as opposed to mimicking the results captures more of this beauty. Competition between individuals and between groups, and ecosystems are necessary as well, which are elements not yet present in this iteration. Although novelty search has biological analogies. The idea of species competition gave rise to this ecology-modeling project as discussed in this interview.

It's worth questioning the very attempt of mimicking as opposed to capturing nature. Where the latter shows deference the former could seem arrogant and delusional. Nothing man has made approaches the complexity of the human body. Perhaps it is the generative artists equivalent to the feeling of conquest that comes from climbing a mountain peak, coming from a deep impulse to dominate nature.

Technically, there is work to be done comparing shape descriptors, reaction diffusion systems and improving the simulation. Looking forward, I would like to provide an artistic simulation engine and benchmark suite for machine learning researchers. Robot control and video games don't need to be the only benchmarks. A Javscript/Webgl implementation would allow distributed computation and interactive evolution. A open source database of fitness functions for other objects would allow the optimization of many types of objects.

Clune, Jeff, et al. "Evolving coordinated quadruped gaits with the HyperNEAT generative encoding." Evolutionary Computation, 2009. CEC'09. IEEE Congress on. IEEE, 2009.

Secretan, Jimmy, et al. "Picbreeder: evolving pictures collaboratively online." Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, 2008.

Clune, Jeff, et al. "EndlessForms. com: Collaboratively Evolving Objects and 3D Printing Them."

Cheney, Nick, et al. "Unshackling evolution: evolving soft robots with multiple materials and a powerful generative encoding." Proceedings of the 15th annual conference on Genetic and evolutionary computation. ACM, 2013.

Bentley, Peter, and Sanjeev Kumar. "Three ways to grow designs: A comparison of embryogenies for an evolutionary design problem." Proceedings of the 1st Annual Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation-Volume 1. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc., 1999.

Kumar, Sanjeev, and Peter J. Bentley. "Implicit evolvability: An investigation into the evolvability of an embryogeny." A late-breaking paper in the second Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference (GECCO 2000). 2000.

Sims, Karl. "Evolving virtual creatures." Proceedings of the 21st annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques. ACM, 1994.

Gierer, Alfred, and Hans Meinhardt. "A theory of biological pattern formation". Kybernetik 12.1 1972: 30-39.

Kondo, Shigeru, and Takashi Miura. Reaction-diffusion model as a framework for understanding biological pattern formation. science 329.5999 2010: 1616-1620

Page, Karen M., Philip K. Maini, and Nicholas AM Monk. Complex pattern formation in reaction–diffusion systems with spatially varying parameters. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 202.1-2 2005: 95-115.

Jones, Gareth Wyn, and S. Jonathan Chapman. Modeling growth in biological materials. Siam review 54.1 (2012): 52-118.

Rudge, Tim, and Jim Haseloff. "A computational model of cellular morphogenesis in plants." European Conference on Artificial Life. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2005.

Merks, Roeland MH, and James A. Glazier. "A cell-centered approach to developmental biology." Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 352.1 (2005): 113-130.

Merks, Roeland MH, et al. "VirtualLeaf: an open-source framework for cell-based modeling of plant tissue growth and development." Plant physiology 155.2 (2011): 656-666.

Kumar, Sanjeev, and Peter J. Bentley, eds. "On growth, form and computers". Academic Press, 2003.

Prusinkiewicz, Przemyslaw, and Aristid Lindenmayer. The algorithmic beauty of plants. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

Lomas, Andy. "Cellular forms: an artistic exploration of morphogenesis." SIGGRAPH Studio. 2014.

Bader, Christoph, et al. "Grown, printed, and biologically augmented: An additively manufactured microfluidic wearable, functionally templated for synthetic microbes." 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing 3.2 (2016): 79-89.

Stanley, Kenneth O., and Risto Miikkulainen. "Evolving neural networks through augmenting topologies." Evolutionary computation 10.2 (2002): 99-127.

Lehman, Joel, and Kenneth O. Stanley. "Exploiting open-endedness to solve problems through the search for novelty." ALIFE. 2008.

Gomes, Jorge, Pedro Mariano, and Anders Lyhne Christensen. "Devising effective novelty search algorithms: A comprehensive empirical study." Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation. ACM, 2015.

Osada, Robert, et al. "Shape distributions." ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 21.4 (2002): 807-832.

Merks, Roeland MH, et al. "Polyp oriented modelling of coral growth." Journal of Theoretical Biology 228.4 (2004): 559-576.

Kaandorp, Jaap A., et al. "Effect of nutrient diffusion and flow on coral morphology." Physical Review Letters 77.11 (1996): 2328.