Beyond Slop

Visions for humane creative AI tools based on

craft, process, and

emergence

Each generation of generative AI fills our feeds with images that look more like each other than like the work of any individual using them. Great for memes, but quickly abandoned. The trendy word for this is slop.

Deep Dream's psychedelic dogs gave way to StyleGAN's endless faces, then VQGAN+CLIP's surrealist mashups, and now diffusion's photorealistic everything.

Responses tend toward breathless hype or reactionary dismissal. The hype says these tools are creative revolutions and the dismissal says AI can never make art1 . I think both fail to imagine how AI can be a better creative medium.

Why is it that clay has more expressive potential than a spirograph? Why can you feel an artist's voice in an oil painting but not a prompt?

As both an artist and toolmaker working with AI (since starting GanBreeder in 2018), I've watched the field narrow around one paradigm. Each generation of generative AI gets better at producing what is in its dataset and increasingly worse at anything beyond it.

I want to build mediums where people discover their own voice. Make things they can call their own and identify with. When someone paints with watercolors - even badly - they're working in a medium with room for a voice to emerge. Ten thousand people can work in oil-paint and develop ten thousand distinct sensibilities.

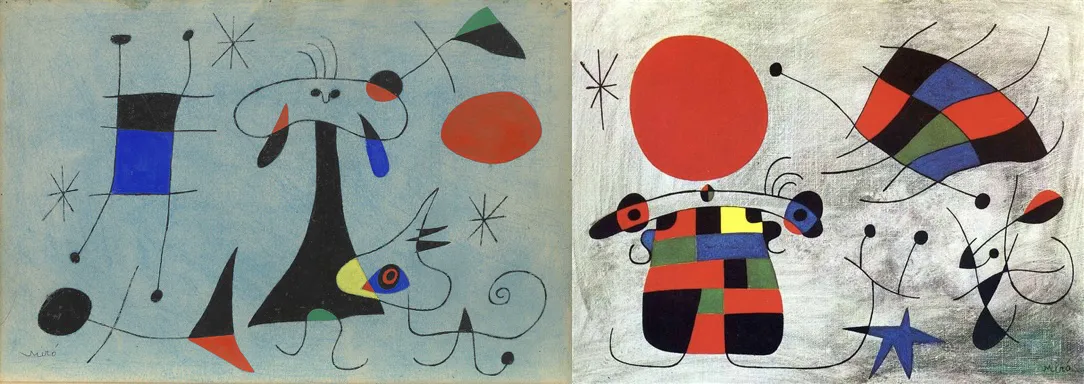

Paintings by Joan Miró2 (left) and Hilma af Klint (right).

I've come to realize3 the problem is in the ideas behind the technology and cannot be solved by better interfaces. Consider how every AI model asks you to specify an input and receive an output. But meaningful creative work doesn't happen that way. It emerges through process - iteration, accident, and surprise. The tools are structured around a model of creativity that doesn't allow for novelty or uniqueness.

When we lock artists inside predetermined styles we're not just limiting what they can make. We're limiting how they think and who they can become. The things we create aren't just outputs; they're how we discover and extend ourselves. A humane tool opens space for that discovery [1] . One that forecloses genuine exploration forecloses a kind of self-discovery.

The aim here is not to pile on against slop—AI dancing cat videos are fun, even joyful. Nor is it to devalue good AI art4 . It's to define these misconceptions precisely, trace their roots, and sketch humane directions for generative AI. The current paradigm is not aligned with what artists need - but is it fixed or inevitable.

The bad ideas of generative AI

Beyond Language

Every generative AI tool asks you to enter text describing what you want to "create". This has been the dominant paradigm since the rise of multimodal models in 2021. However, it has been a great mistake to confine visual expression to language.

Language is great for referencing what already exists, but incapable of describing a style that hasn't been defined - using it is more like querying an infinite library than an act of creation. You can easily prompt for "cyberpunk dog on a skateboard" because every component points to known existing concepts. But you cannot prompt for the genuinely new: the thing that doesn't yet have a name, the aesthetic that hasn't been articulated. If you gave ten artists the same prompt you would likely get ten very different outputs, because interpreting the prompt is where the creative work happens. The prompt box is a cage formed by existing vocabulary.

Beyond Control

The field has tried to overcome language by adding more controls: reference images that guide composition, style, or likeness. I used to think control was the missing piece, and developed several tools for generative control.

But control over what? Submarines and tractors have many controls. That doesn't make them expressive mediums. Add a million knobs to a machine and its output still won't feel like part of you.

A synthesizer has endless parameters and is deeply expressive. But its controls shape an ongoing process: sound evolving in time. Diffusion controls are more like the submarine - steering toward a destination that exists in the model's latent space. The controls help you arrive faster, but the destination was always defined by someone else.

Beyond Imagination

These bad ideas converge in a common marketing slogan: "Bring your imagination to life." It sounds great, exactly what creative tools should do, right? (Grok has even named their generative tool "imagine.") But this assumes your ideas already exist, fully formed, just waiting to be rendered.

Creativity often starts with a vague hunch born from deep engagement with a material. During creation you respond to what you see, improvise, and discover as you work (which is often where the joy is). The more time you spend with wood, the more ideas you'll have for what to make with it.

Generative AI tools are structured as mappings of inputs to outputs. This presupposes the idea exists fully-formed before the tool touches it. But creative processes help discover the unimagined.

Beyond Mapping

In every AI art tool the core mechanic is the same: you provide an input and the system maps it to an output. Prompt→image. Image→video. I call this the "X→Y" or "mapping" paradigm: creative tools as transformation between defined states.

This mapping ideology is rooted in machine learning itself. Models work in latent "spaces," and the field treats "space" as a core organizing principle. When you prompt the model it gets embedded into a space of language. When you use an image as a style reference it gets embedded into a latent space of styles.

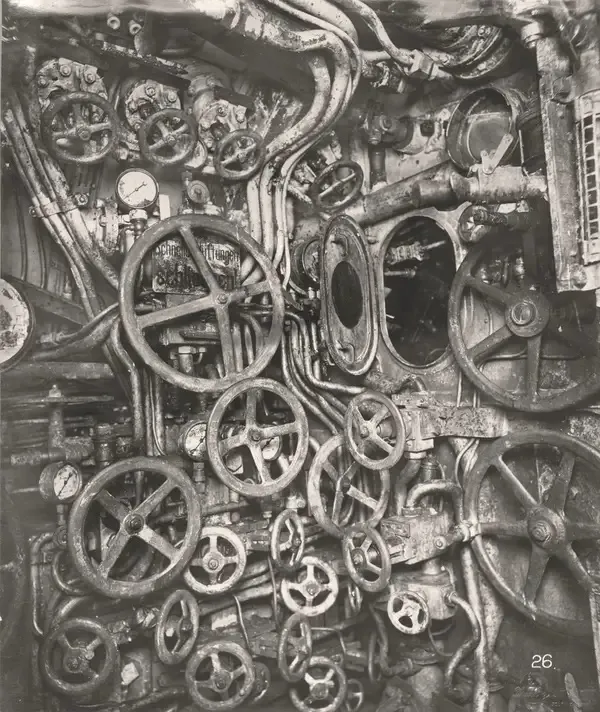

Left: Jackson Pollock's Studio; Right: Alexander Calder's.

Pollock's style wasn't merely a point in latent space. It was his unique process: the drip technique, the canvas on the floor, the full-body movement. A style is an expansion of the map, not a point within it.

Same with Alexander Calder's mobiles. He developed custom tools, special calipers and balancing systems, that allowed him to work with equilibrium as a medium. [2] The mobiles aren't a style you could apply to other objects. They're the output of a specific process that he invented.

If styles are processes, then artworks are the results of these processes. In a 1956 documentary, Picasso was filmed painting [3] . What he made shifted as he worked: a chicken became a vase, the vase became a face. Maybe he was being cheeky for the video, but I think it illustrates something deeper about how the final image couldn't exist without traversing those steps. It carries the history of its own making, and that history is the source of its complexity.

Le Mystère Picasso - full video

Think about the last time you made something with your hands: cooking, woodworking, sketching. What made it satisfying? The way the rough squiggle evolved into a form. The happy accident that gave you an idea to build upon. The moment you surprised yourself by discovering what you were actually making, halfway through making it.

Anyone with a developed creative practice knows this intimately. The joy of clay isn't producing a pot; it's the budding of an intuition into a resolved idea as you think with your hands. The drawing isn't the point. The drawing is a residue of the real thing, which was the process of drawing.

Creation is the result of an open-ended process.

This is so obvious to practitioners that it feels strange to state. And yet the entire generative AI paradigm is built on eliminating exactly this. We are essentially building molds with dials rather than clay. Describe what you want, receive the thing. But the interactive process with the material is where the meaning is.

Not all processes produce emergence. You can iterate on a prompt a hundred times and it won't be novel. This is true even for graph-based workflows: chaining X→Y→Z doesn't produce emergence, it produces a constrained walk through predetermined space. Going off manifold requires a different kind of process entirely.

Irreducibility

There's a theoretical frame for why this might be necessarily true. Not just a matter of preference, but something deeper about how novel forms emerge.

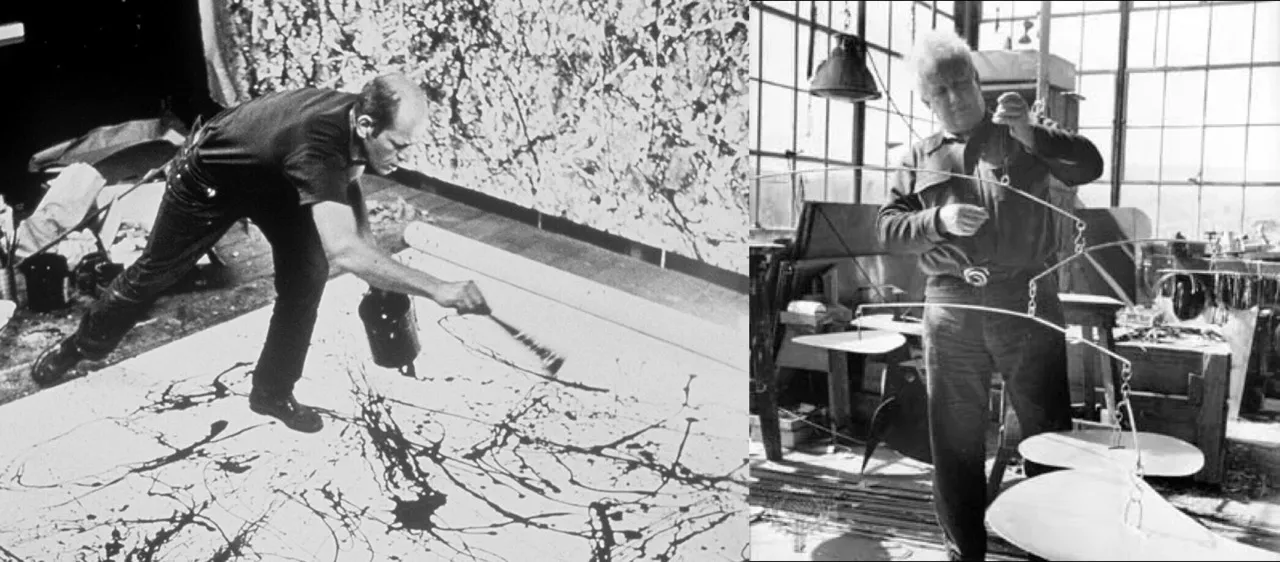

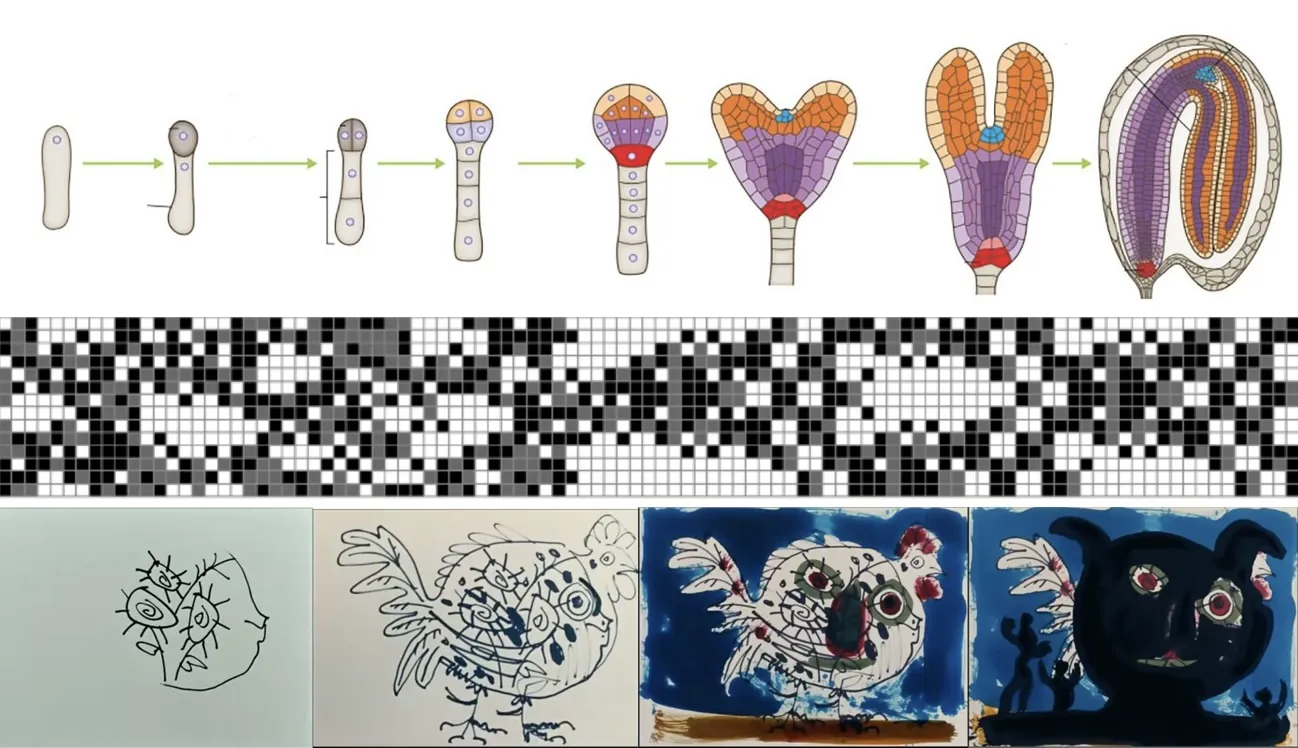

The mathematician Stephen Wolfram has a concept called computational irreducibility [4] . Essentially saying that simulations cannot be shortcut. To know what a cellular automaton will look like after a thousand steps, you must run the simulation step by step. The same is true of biological growth. You cannot compute what a tree will look like by analyzing the seed. The form emerges through an irreducible process, producing outcomes that couldn't have been specified in advance.

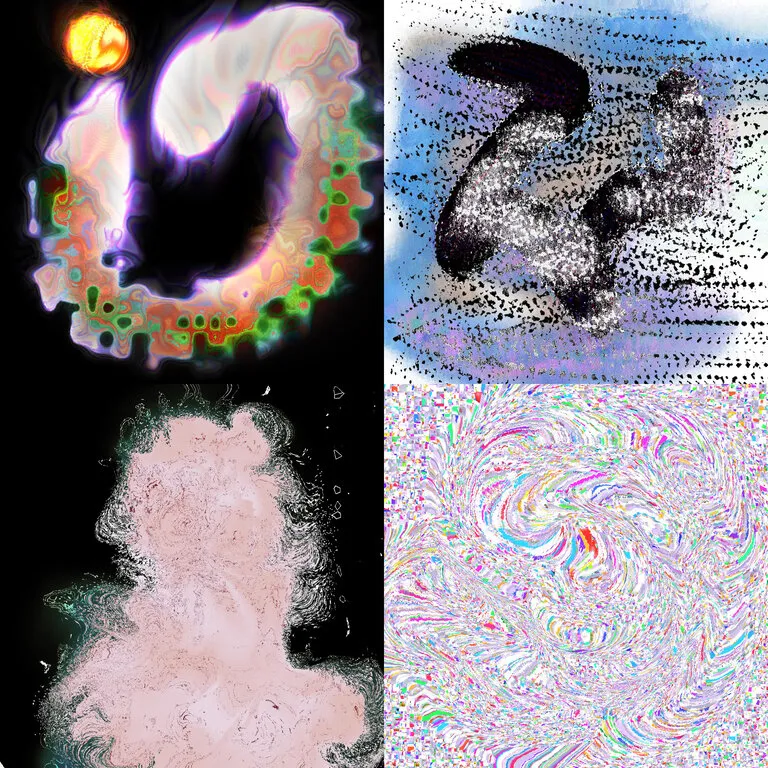

Irreducible processes: embryonic development, cellular automata, Picasso painting.

The architect Christopher Alexander expands this insight in "The Nature of Order." [5] He describes a universal process of sequential transformation that gives rise to the forms of cities, organisms, and artifacts. Alexander traces the opposing view to Descartes and the "mechanistic" tradition. The mechanistic perspective says you can understand a clock by decomposing it into modular parts: springs, gears, escapements. But you cannot build a tree out of leaves. Most complex forms can only be understood through the emergent processes that created them.

Generative AI embodies the mechanistic perspective. It assumes an image can be decomposed into "style" and "composition" components, that creativity is modular and recombinant. But if Alexander and Wolfram are right, you can't get emergence from decomposition and mapping of existing spaces. This is the distinction at the heart of slop: creation as mechanistic mappings versus human-driven emergent processes.

Experiments in Process

Since 2018, and with my studio Morphogen, I've built a series of experimental interfaces trying to make playful and accessible creative tools out of new technologies.

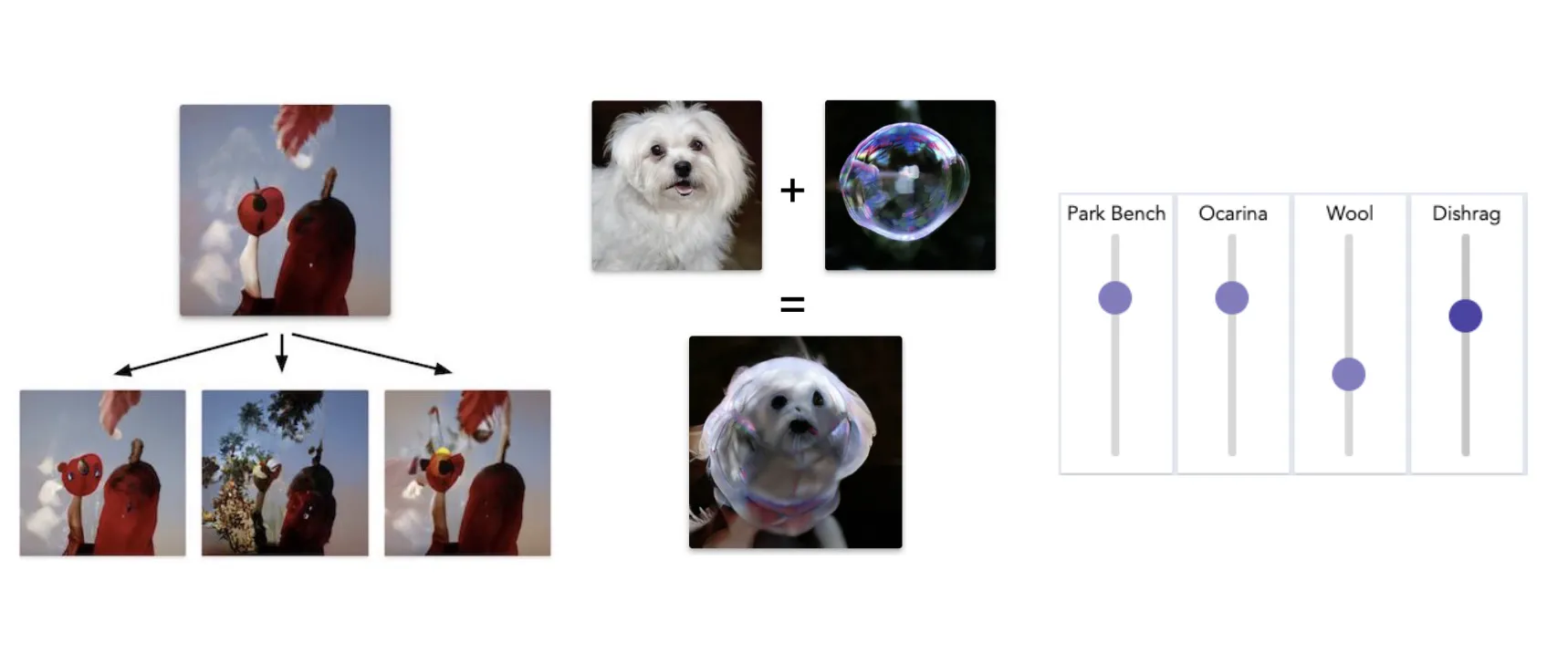

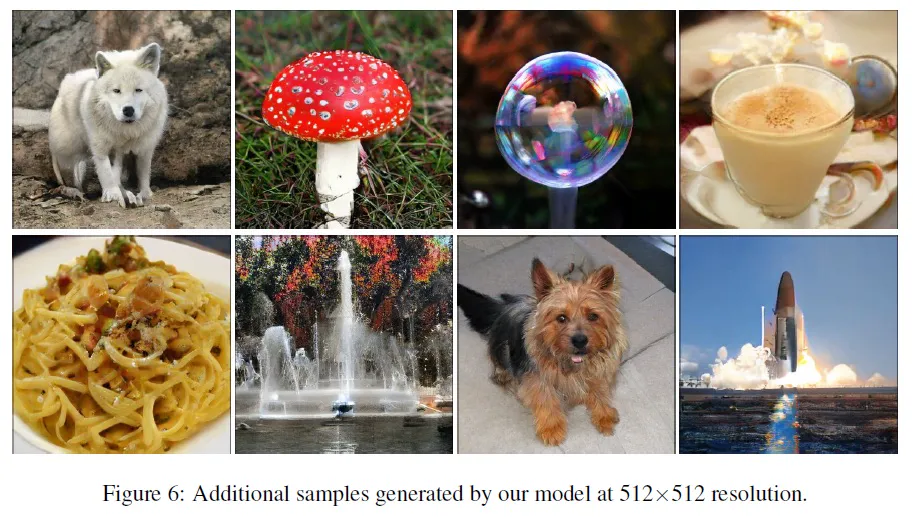

Artbreeder (originally called GanBreeder) started in 2018 as an attempt to wrap the then-new GAN technology in a radically simple and playful interface. The standard interface for GANs at the time was to input random numbers and receive an image.

Inspired by Picbreeder [6] , a seminal project in open-ended collaborative discovery5 , the interface is organized around breeding and biology. You take an image and create variations of it (children), mix two images together to get offspring, or tweak sliders that function like editing genes. And everything is social and collaborative — users fork your images, breed them with their own, push them in new directions. The whole platform became a collective exploration of latent space.

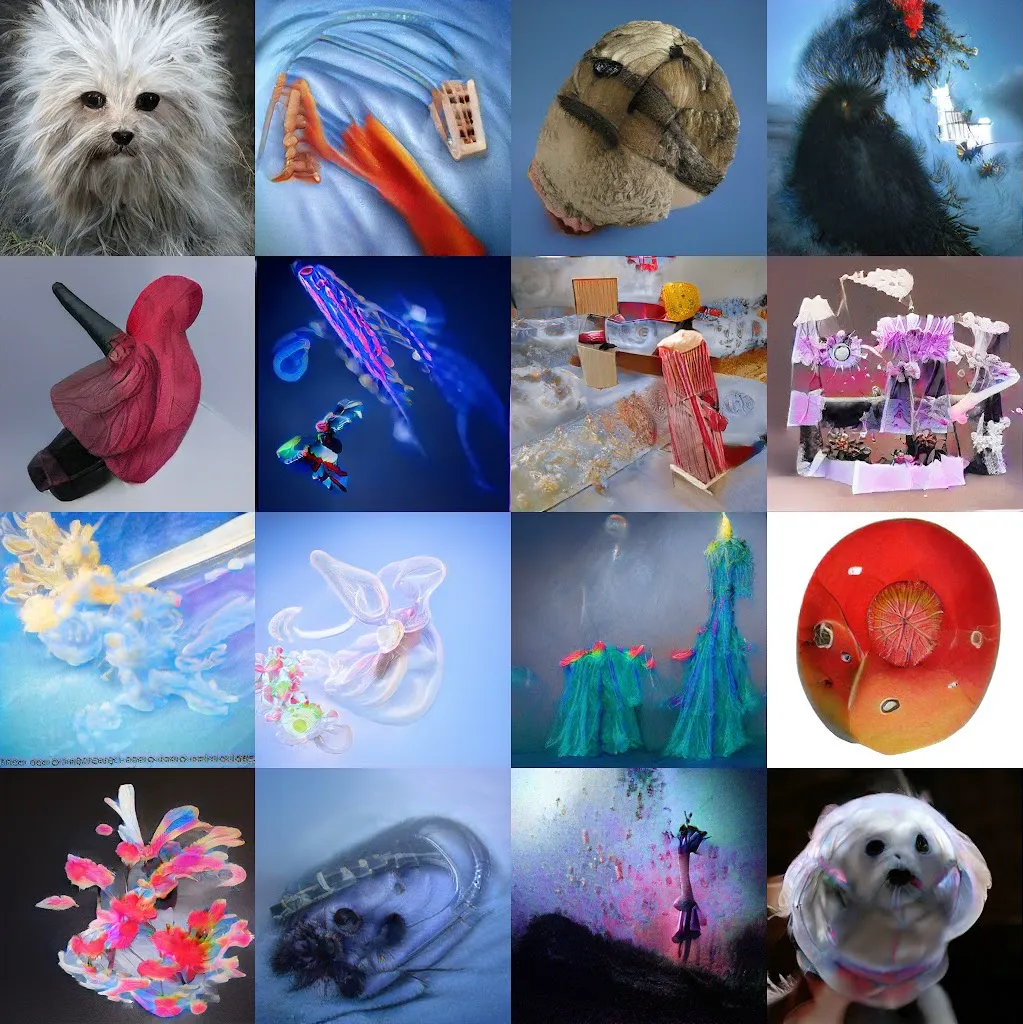

BigGAN sample images left and GanBreeder 2019 right

The images people found through breeding were substantially different from the semantically simple ones the GAN paper had showcased. The trending page on ArtBreeder was full of strange hybrids, impossible landscapes, forms that felt genuinely new. Things nobody would have thought to prompt for, discovered through collective exploration.

What was most meaningful was that multiple artists got their start on ArtBreeder, developed distinct voices and graduated to sophisticated processes with multiple tools

Interviews with artists who developed their practice on Artbreeder

As the platform went mainstream with 2020 TikTok virality and portrait models were released, usage shifted toward imitation: people recreating existing characters, turning fan fiction into images. The breeding metaphor enabled exploration, but it didn't guarantee novelty.

Puppets

Artbreeder's success was used to fund Morphogen, a studio dedicated to building expressive creative tools. By 2021, feeling sick of AI images, we initiated Puppets to ask: could AI content ever feel homemade? Could the hand of the creator be present in the output?

Puppets.app is a browser-based collaborative puppet theater inspired by traditional craft and childlike play. Users could cut out paper-craft puppets, rig them with pins and springs, and perform with them in real time, including performing into diffusion models, controlling AI-generated video through gesture and movement. We wanted to capture the group sandbox feeling, where it's more about the joy of improvising together than the quality of the output.

Left: Puppeting diffusion process. Right: real time collaborative improvisation.

A prompt can describe a fish. It cannot describe the particular way you would make a fish jump out of water: the timing, the arc, the personality of the movement. That's knowledge that lives in your hands, not in words.

ProsePainter and Collager

ProsePainter and Collager were among the first diffusion interfaces that attempted to resist the prompt box and make diffusion feel more like a medium. ProsePainter incorporated guidable text-to-image generation into a traditional digital painting interface. Collager let you cut up noise masks and inject them into the diffusion process, steering generation through shape and texture rather than words alone.

ProsePainter 2021 @Morphogens

Collager 2022 @Morphogens

We have since released multiple tools for latent space exploration 6 which enables exploring the spaces "between words" as well as co-develop tools for advanced control with artists 7 .

Malleable mediums and custom tools

Brushbloom and ProsePainter2, are two experimental creative tools that explore the ideas that emerged from this work: expressive mediums are malleable and enable custom tools and processes.

Brushbloom is a digital painting app with custom rendering engine where the brushes are generative WebGL shaders you can prompt for, breed, and share.

ProsePainter2 continues the vision of the original. It is a painting tool build from the ground up around around diffusion. Instead of the typical representation of red, green and blue, it stores its canvas as "pixel-latents" and "controlnet-layers". Additionally, you can mix your own "paints" from text and iteratively repaint without losing information, growing forms through gradual emergence rather than one-shot generation. Can browse outputs here.

Iterative repainting, color guided diffusion, canvas expansion and custom paint mixing.

In both tools you can share not just your timelapse videos but your paints and brushes with others. In a recent workshop in San Francisco, a group explored crafting their own tools and processes and sharing them with each other in a symbiotic network of co-inspiration.

Toward New Research Questions

The tools I've described all worked by exploiting margins in systems that weren't designed for craft or process-based creation. Artbreeder used negative class inputs, Collager hacked the diffusion process, Artbreeder repurposed embedding layers. These were happy accidents of early implementations, and most have been optimized away in newer models. What if the model architectures were actually designed with this in mind?

The problem starts with how research defines success. Generative AI research optimizes toward benchmarks, and the dominant ones measure image quality (scores like FID) and prompt adherence (CLIP similarity).

What would it mean to design a GAN to have rich extrapolative ability? How do we even evaluate latent spaces as vast, rich territories for exploration rather than distributions to sample from? We don't even have the language or metrics to explain why some latent spaces feel rich and explorable while others feel shallow.

In the original CLIP+VQGAN work, you could optimize toward any loss you wanted, not just text similarity. Loss functions aren't bounded by datasets the way latent spaces are. They're a different kind of creative material entirely. I explored this in projects like Dimensions of Dialogue and derivative.works, where the optimization function itself became the expressive medium. This is just one example of alternative paths to the mainstream.

What does the scalpel of a gaussian splatting look like? What is the paintbrush of a pixel-VAE latent? What does the tool that lets users build their own tools look like?

If we want more humane tools, we need to stop optimizing content generators and start creating malleable materials that enable craft, process, and genuine creative emergence.

Conclusion

We need to dispel the myth that image quality and prompt adherence are proxies for creative potential, that mappings are a substitute for process. What's needed are malleable, open-ended mediums that let you develop and express your own voice. Processes where you can improvise toward something you couldn't have imagined beforehand.

We will know when this is working when we can clearly identify one artist's style from their work alone. When artists don't worry about sharing their prompts because they do not determine the output. When we judge models not by their adherence to existing style but capacity for emergent ones.

There's more openness to this than you might expect. When I presented a version of these ideas at CVPR 2025, some researchers resonated with the critique, and others said they'd never considered it, that it completely changed how they thought about the field. The problem hasn't been properly defined, which means it cannot yet be solved. But the conversation is possible.

Those of us working with these models before 2021 remember when the space felt wider. Most people entering the field now only know generative AI as it is, not as it could be. But each new medium enables new artists, and different kinds of tools and materials are possible. The question is whether we keep building molds with dials, or whether we make clay.

Footnotes

References

- [1] Bret Victor. "The Humane Representation of Thought" Dynamicland.org, 2014. [link]

- [2] "Calder and His Mobiles." The Gordon Parks Foundation. [link]

- [3] Henri-Georges Clouzot. "Le Mystère Picasso." 1956. [link]

- [4] Stephen Wolfram. "Computational Irreducibility." Wolfram MathWorld. [link]

- [5] Christopher Alexander. "The Nature of Order." Oxford University Press, 1979.

- [6] Jimmy Secretan, Kenneth O. Stanley, et al. "Picbreeder: Evolving Pictures Collaboratively Online." CHI '08: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2008. [link]